Paul, Paradox, Myth, and the Danger of Knowledge

“Paul, you are out of your mind! Your great learning is driving you mad!”

So exclaimed the governor Festus on hearing Saint Paul speak.

Until recently, this statement made sense to me. Studying too much can push some people over the edge. But lately, I’ve started to wonder if the whole concept behind this outburst isn't tied up with ancient paganism.

After all, shouldn’t learning be a good thing? Isn’t learning good for everyone?

Apparently, the ancient pagan world didn’t think so. The great philosophers taught the elite, the sons of kings. Plato advocated “benevolent deception” of others. Meanwhile, the Jews were instructed to teach their children, writing the most sacred information on their doorposts.

Maybe there’s something fundamental here. Maybe there’s something core to the ancient pagan worldview, that caused learning to be dangerous, toxic, self-limiting.

My mind is drawn to the statement “All Cretans are liars,” made by the Cretan Epimenides. This is called the Epimenides Paradox, and is interpreted as a form of the self-contradictory claim “This statement is false”.

Paul would have known about this logic puzzle. Whether or not the irony of the statement was intended by Epimenides’ original words, by Paul’s time, the logical form of the puzzle was already being discussed in the Greek world.

And interestingly, Paul quotes Epimenides twice in the New Testament.

The first is when he is standing in Athens, on Mars Hill, at the center of the Greek philosophical world. Here he makes a case for his form of monotheism, by citing a statement from Epimenides, “In him we live and move and have our being”.

The second is in Titus 1:12, where Paul quotes the source of the Epimenides Paradox itself—a statement that has been widely interpreted as meaning, “This statement is false”—and then follows it up with the mind-bending comment, “This statement is true”.

What is Paul doing? Is he letting us in on an incredibly nerdy philosophical joke? Is he affirming the paradox as fundamental in some way? Is he denying the interpretive premise of the paradox? Is he telling us something about the pagan world?

Or is he doing all of the above?

In context, he’s warning against those who were peddling myths. In Athens, he was warning against those who were peddling idols. In both cases, he turns to Epimenides to speak to the problem.

The Epimenides Paradox relates to one of the most significant theorems in logic: Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem. Gödel’s Theorem shows that there can ultimately be no closed, self-contained systems—because all systems contain something analogous to the Epimenides Paradox.

This shattered a long-held hope of philosophers and mathematicians. And was held to have wide-ranging social and philosophical consequences.

For example, some have suggested that Gödel overturns the very concept of a rule-based ethic. Once you establish a set of rules for determining right and wrong, then, per Gödel, you also establish a set of actions whose ethical value can never be determined.

In other words, Gödel may not just have shattered the dreams of mathematical philosophers, he may have shattered the dreams of millennia of religious scholars as well.

Douglas Hofstadter, in his famous book Gödel Escher Bach, argues that the power of this self-referencing circularity reveals something about consciousness and AI. Self-consciousness seems like the kind of self-referencing that leads to this paradox in the first place. And so Hofstadter, for hundreds of pages, strives to show us what self-reference really might contain.

But if this kind of self-referential circularity is so core to mathematics, to science, to consciousness itself—why is it so terrifying?

Because, as Gödel proves, this kind of circularity allows a system to destroy itself. A snake can eat its own tail. A Cretan can condemn his whole nation, and himself in the process.

This leaves you with only three options.

One, burn it all down.

"Everything is meaningless! says the teacher."

If no system can be consistent and complete, then there is no foundation to truth. It's not turtles all the way down—a futile explanation for a futile problem—it's simply nothingness, a leaning over the edge, a staring into the void.

Two, flinch.

Look away. Close your eyes. Pretend it's not true.

If your system can't be self-contained, just pretend it is, shout down the contrarians, destroy those who get in the way.

"Better one man should die, than that the nation be destroyed."

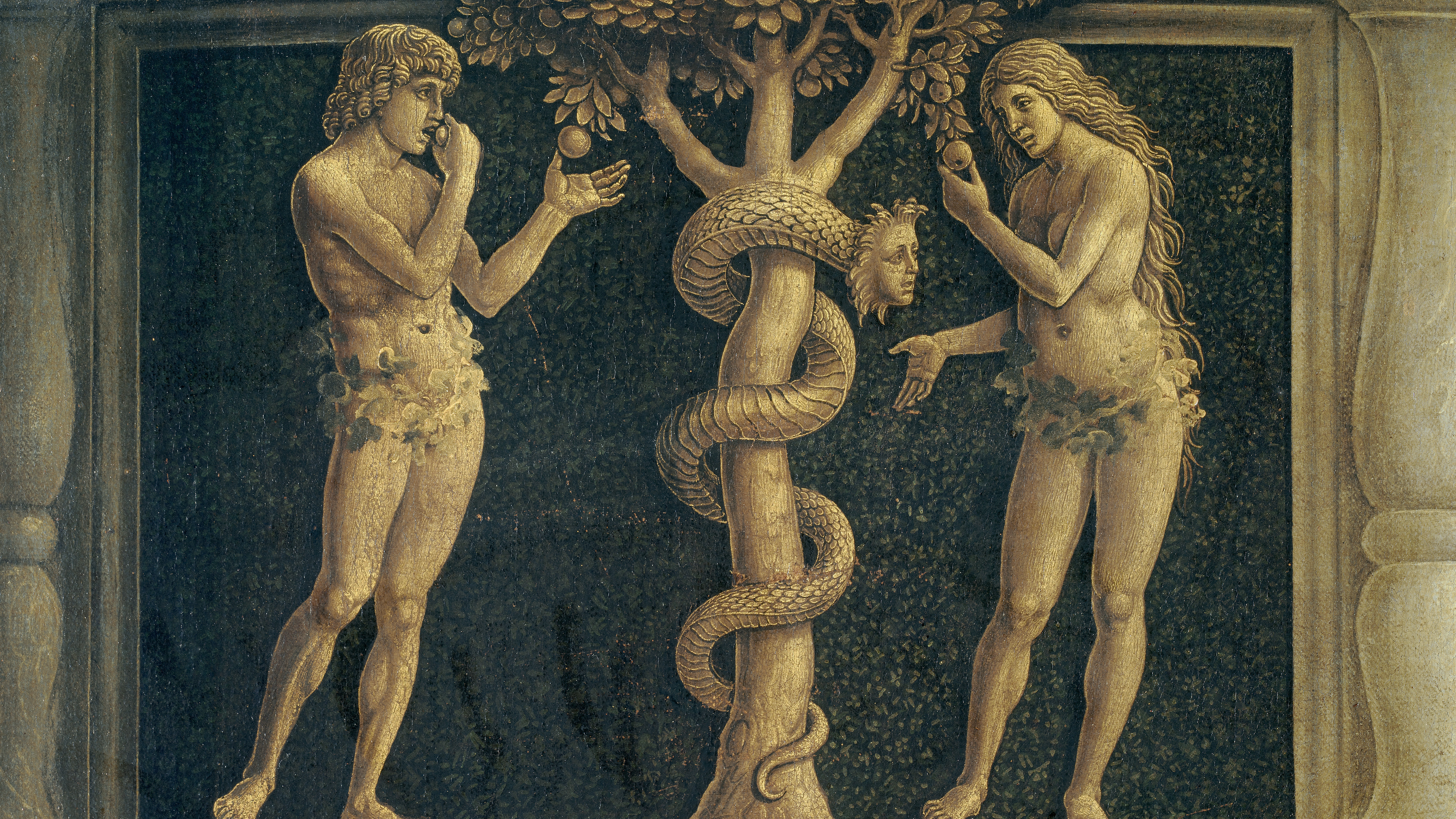

From the time of Cain til today, the great pagan dream was to build a walled city, a closed society, a self-contained system with no change, and no relationship to the outside world. This was the dream that drove Babel, and fueled Plato. This is what made the pagan gods torture Prometheus for bringing fire to man.

But no closed society can eradicate circularity, and thus every closed society is at risk of being destroyed.

Unless it can learn to lie.

Unless it can learn to look away.

Unless it can learn to question only so far—and then no farther.

A closed society creates a closed mind.

But a closed mind must work the same way. No outside thoughts, no outside forces. Everything needed is already contained within. You can search out ancient knowledge, you can study the known works, you can ask big questions. But question too much, and you might cross an invisible and dangerous line. You might invite in an outsider. You might find something troubling. You might unleash the chaos.

And so you learn to lie.

You learn to look away.

You learn to question only so far—and then no farther.

So you can see why, faced with something unheard of before, a leader in the ancient world would have assumed that in deep study, some unknown line had been crossed, and all chaos had broken loose.

Or...

Three, throw open the gates.

Build an open society, an open and evolving system, a system of concepts and symbols and meanings that make sense, but are not wholly self-contained, nor closed off to the outside world.

This system cannot eliminate circularity either. Instead, it must use circularity as an excuse to build outward, to embrace a stranger, to expand the circle of concern.

This statement is true—and it is true within the larger sphere of life we must now embrace.

In Paul's thought, the resurrection is not simply a moment in time where the ancient myths are reversed, and the dead refuse to stay dead. It is a moment in which the closed self-circularity of the world must break open, and infinite knowledge and learning and creation must pour in.

...

This essay assumes some familiarity with:

Girard on Myth

Popper on the Closed Society

Hofstadter on Self-Reference and Paradox