The Infinite Morality of Jesus

In his book, The Beginning of Infinity, David Deutsch argues that there are moments when something switches from being of only limited and local use, to having infinite reach.

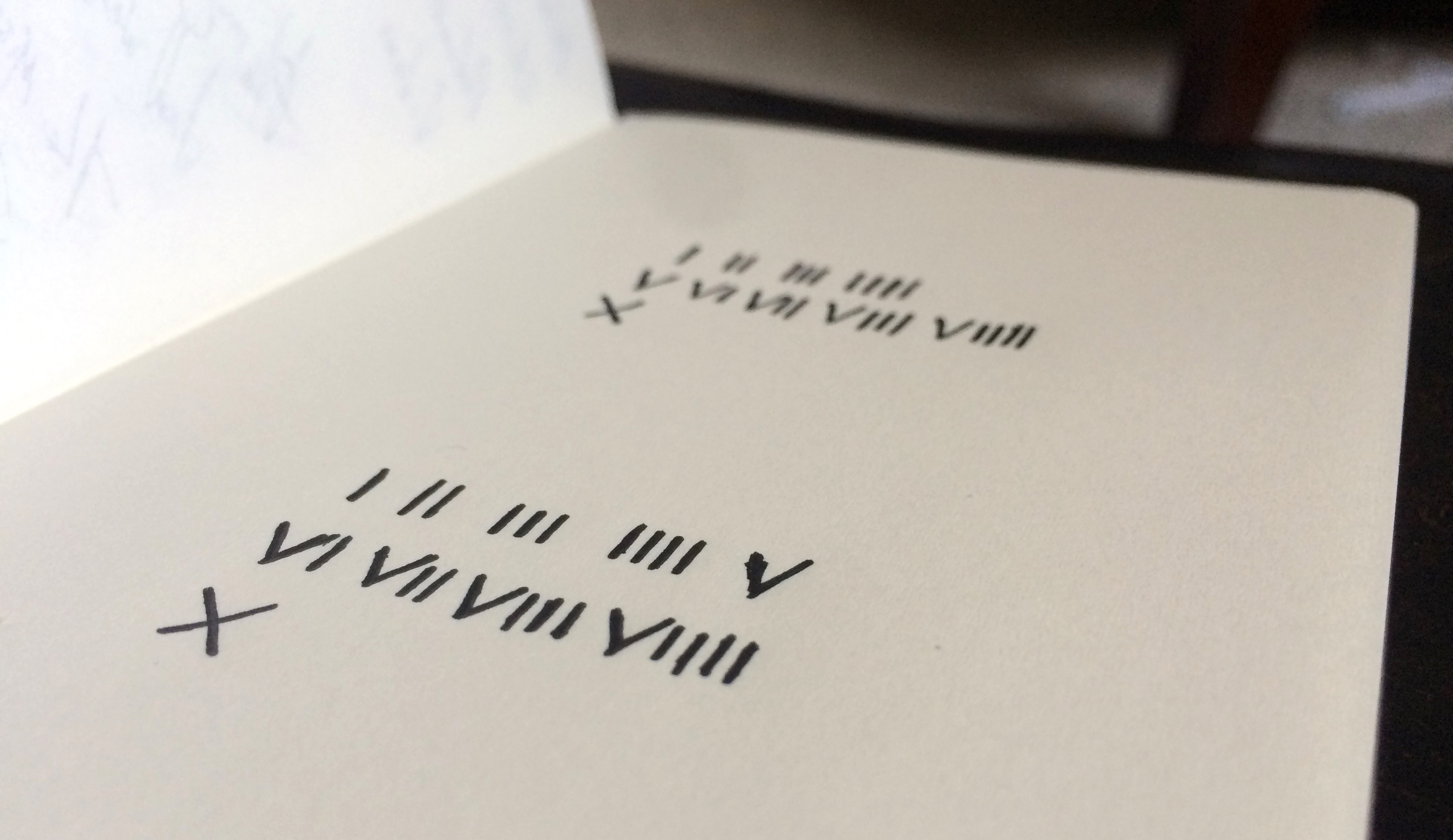

If you’ve ever played around with Roman Numerals, you’ve experienced a bit of this.

As a kid, I loved Roman Numerals. They were sort of a secret code, and at the same time, they made a kind of sense that regular numbers just don’t make. Roman Numerals were perfect for carving into stone or a piece of wood, and because they were just based on adding together larger and smaller values, they were highly intuitive.

The idea is simple: you start with a symbol for “one”. For two, you write two symbols. For three, you write three symbols. When you start getting to the point where the symbols are getting a bit unwieldy, you invent a new symbol. So now you write “V” instead of five ones, and you continue as before.

One? I

Two? II

Five? V

Six? VI

Ten? X

Twenty? XX

One thousand? M

Two thousand? MM

But if you try to deal with large numbers, you run into problems. How do you represent one million? Would you line up a thousand M’s? Would you just keep inventing new symbols? What happens when you run out of symbols that are easy to write, or easy to tell apart?

It quickly becomes apparent that Roman Numerals, as nifty as they are, don’t scale. They aren’t appropriate for dealing with the number of people in a city, much less the numbers needed for economics or physics. The core limitation is that Roman Numerals need a totally new symbol for every order of magnitude (ones, fives, tens, fifties, hundreds, thousands). And so, no matter how many symbols you create, it will never be enough.

Arabic numerals, on the other hand, don’t suffer from this problem. They use something called place notation. This means that we don’t need a new symbol for every order of magnitude, we just need to shift one step to the left.

1

10

100

1000

10000

100000

…

You get the point. Where Roman Numerals were limited by the number of symbols that someone could etch into a rock, Arabic numerals have unlimited reach. They can represent literally any number imaginable, and never require any new symbols to be invented.

As I see it, the Law of Moses is like Roman Numerals, and Jesus is like place notation.

The Law of Moses, in so many ways, was great. It addressed every aspect of human life. It gave straight-forward answers to difficult questions. It created unity and cohesiveness and social strength, perhaps at a level that has never been matched.

But if you read it, you can see its limits. It contains instructions on roof building, clothing, and food that only make sense in the ancient desert. It doesn’t address electricity, bioethics, democracy, or any number of other issues that have come up in the last 3000 years.

Many people have tried to rectify this situation. Some rejected modern society, and took up an ancient way of life, hoping it would fit with the Mosaic Law. Others tried to slice up the Law in some way, applying pieces of it strictly, and other pieces not at all. Still others focused on the big ten (the 10 commandments) and asserted that they were the really important part.

None of these approaches can escape the fact that the Law of Moses was created for an ancient tribal society. Even those who try to recreate the lifestyle of 2000BC can’t recreate an entire nomadic tribe — and consequently, they can’t actually practice the core of the Mosaic Law: the tabernacle and its religious sacrifices and rituals.

Jesus, however, established a different sort of system. He redefined almost every concept in the Law to be related to intrinsic motivation and aim. He boiled down ethics to “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength…and love your neighbor as yourself”.

In doing so, he created a system with infinite reach. While the Mosaic Law wouldn’t work outside of the ancient desert, Jesus’ morality would work just as well in the Andromeda galaxy. While the Mosaic Law couldn’t address new situations, Jesus’ morality could address any situation imaginable.

For example, when asked about matters of ritual cleanliness (a big deal in the Law), he said:

Listen to me, everyone, and understand this. Nothing outside a person can defile them by going into them. Rather, it is what comes out of a person that defiles them…(In saying this, Jesus declared all foods clean.)…For it is from within, out of a person’s heart, that evil thoughts come—sexual immorality, theft, murder, adultery, greed, malice, deceit, lewdness, envy, slander, arrogance and folly. All these evils come from inside and defile a person. (Mark 7:14-23)

It is one thing to tell people that (say) bacon is no longer unclean. It is another thing to say that there will no longer be any foods which are unclean. And it is still another thing to challenge the basis of the entire rule itself.

This is what Jesus does, not only moving away from clean and unclean foods, but moving away from regulations based on exterior actions. In Jesus’ framework, the things which have moral significance are things which arise in the core of a person and spread outwards.

This means that morality is no longer based on your environment, but on you. And so, suddenly, “clean and unclean” stop being categories which refer to a finite list of things and activities, and become categories which can operate across the universe.

Jesus doesn’t stop there. He does the same thing with questions of adultery, lying, covetousness, and even murder. And when asked for the greatest commandment in the Law, Jesus replies:

‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’ This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments. (Matthew 22:37)

The last line is crucial. Jesus is stating that love is the core of the Law, and everything else is implementation.

Paul, the main expositor of Jesus’ message, picks up on this theme.

Let no debt remain outstanding, except the continuing debt to love one another, for whoever loves others has fulfilled the law. The commandments, “You shall not commit adultery,” “You shall not murder,” “You shall not steal,” “You shall not covet,” and whatever other command there may be, are summed up in this one command: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” Love does no harm to a neighbor. Therefore love is the fulfillment of the law. (Romans 13:8-10)

For the entire law is fulfilled in keeping this one command: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” (Galatians 5:14)

In my experience, Christians often pass over passages like this as if they were insignificant. But they weren’t insignificant to the early Christians: they were the core of a revolutionary new understanding of faith that promised — for the first time in history — a morality that could work across the entire world, and then keep going, on to infinity.

“Heaven and earth will pass away, but my words will never pass away.” (Matthew 24:35)

If all that Jesus and his followers had done was to update the rules to apply to a new situation — if all that had changed was that one set of commands was replaced with another set of commands — then Jesus’ morality would not be unique or special. It would be just another moral code amongst the moral codes of other great teachers and leaders.

But Jesus does more than this. At a fundamental level, he does away with finite rules and laws altogether. And he replaces them with an infinite motivation, one that makes every other ethical and moral system redundant — one that calls to bigger and better things than had ever been conceived before.

From this point on, there is a new fundamental. Human nature may change, the earth may change, the sun may burn out and the galaxy dissolve. But whatever kinds of life there may be in our future, they will be defined by their reaction to a core motivation — a motivation that, recognized or not, is the infinite morality of Jesus.