In this series:

Deus Ex Machina

In Insurrection, Peter Rollins critiques the Deus Ex Machina.

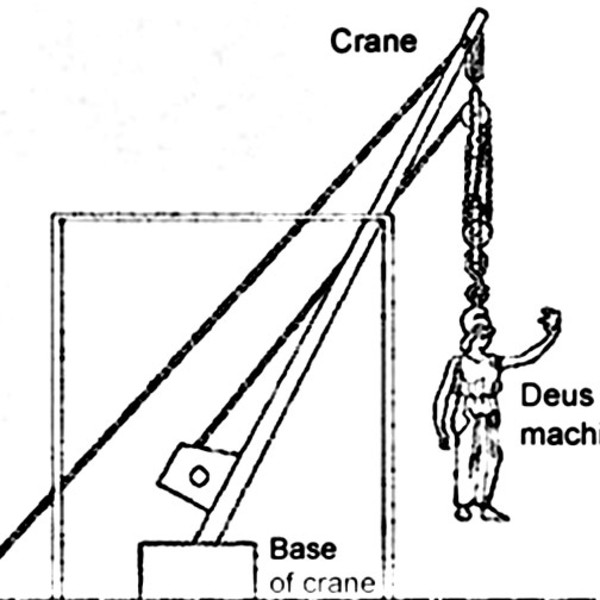

This is the god that, in ancient Greek plays, was lowered on a rope into the middle of the stage, in order to resolve the story. It's a terrible contrivance, and we've probably all seen bad movies that make use of just this sort of device. Perhaps it comes in the form of a fairy godmother, or someone winning the lottery, or someone waking up to discover that the whole episode was a dream.

What makes this so abhorrent is that it invalidates everything else in the story. We are tracking along with the characters, experiencing their desires and struggles, watching everything run on a collision course towards the center. We hold our breath, waiting to see what will happen. And then the stagemaster cranks in his cheesy plot device. The story has just been destroyed.

It's worse because we know we can't rely on such devices in our lives. If we get late on our bills, we can't just win the lottery, or whisk in a fairy godmother. We actually have to struggle through the issues, solving problems by weaving together the strands of our desires and abilities and choices. In investing ourselves in a story, we are trusting that the author will do the same thing, working with the same threads we have, and in the process, showing us a way forward.

The problem isn't with the supernatural itself. We enjoy movies about wizards and vampires and superheroes. But when those stories are done well, the supernatural isn't the mechanism by which problems are solved - it's the mechanism that causes the problems in the first place. If Harry Potter could have simply cast a spell and solved all his problems, there would have been no story.

Peter Rollins suggests that all religion promotes the Deus Ex Machina. Whether extreme fundamentalism or feel-good Christianity, religion trots out a God who appears whenever we need reassurance, confidence, or purpose in life, and who otherwise gets cranked back up into the rafters. Rather than doing the hard work of finding true meaning in our existence, we can rely on this much easier and more convenient fallback mechanism.

This dynamic works itself out in the church. Once a week, we are offered the chance to step into an alternate world and truly experience the presence of God, in a thin space which operates to free us from the cares of this life. But if this effort is successful, we may well end up addicted to ever-more ecstatic worship experiences. The more successful we are at bringing God near in these unique moments, the more the color and meaning is drained from the rest of our lives.

I've detailed this here. A God standing outside our world will always draw us away from normal life, sucking the meaning right out of existence and into a world far removed from our own.

Rollins' solution to this, and one that I endorse as wholly biblical, is that we must come to see God not in some external reality, but as being present in the very act of love. Rather than an object of affection, God becomes the means by which we love others.

But there is a problem. Many of the people who embrace this approach are unable to see how God could then be real in any sense. God becomes a personification of love, and loses all substance. Richard Beck has suggested that while this losing God, finding love thing might have some validity, it might also cause you to commit suicide. Instead of making a choice between a transcendent God and a God present in love, couldn't we have both? Or as Daniel Kirk says, maybe it's not either-or, maybe it's both-and?

This is a very common refrain among postmodernists, and it's one I inherently distrust. It seems to me that if there are legimitate tensions between two ideas, we shouldn't just go smacking those ideas together and calling it good. There is a reason for the tension, and it demands that we figure out why.

But I, for one, do believe in a real God. And I also think Pete is right to suggest that focusing on a metaphysical world devalues life. And I also think Richard is correct to point out that simply abandoning your ground of being is a good way to end up killing yourself.

So what alternatives are there? Is there a way to believe in a real God, and yet not get sucked into the metaphysical trap? Is there a way to affirm God as being present in love, and yet not lose God as real?

I think there is a way, and one that seems to have remained relatively unexplored.

Rollins places God firmly in the actual mechanics of our love towards others. In the biblical narrative, we can say this is true because God placed himself there. God, desiring to draw us into the world, made it so that our affection for him always has to go through something else.

It is as if he placed the entire world between us and him, and said "Now love me!" And so our love, as a result, has to hit everything in between.

But this is not the entirety of our experience of God, because God loves us back. And so God's love comes to us, back through the world, humanity, and the rest of reality. This experience of love can never be entirely localized or constrained, because it comes to us from all directions, an omnipresent downpour.

This draws us firmly into the world, because we cannot love God without loving the world. But neither can we experience God's love apart from our experience of the world. That love can never be reduced to a specific entity or location, but is always experienced in specific entities and locations.

God is real because love comes to us. God is experienced when we direct that love towards others.

This is what saves our love from becoming idolatry. This is what saves God from becoming a flattened abstraction of our own sentiments. This is what gives us an alternative to metaphysical obsession.

And this is how God comes to us not as the Deus Ex Machina, but as the very dynamic of the play itself.

Peter Rollins and Insurrection: